High and Lonesome on the Blue Ridge Parkway

With so many routes in the United States scarred with motels, billboards and more, this stretch from Virginia to the Great Smoky Mountains is like a trip back in time.

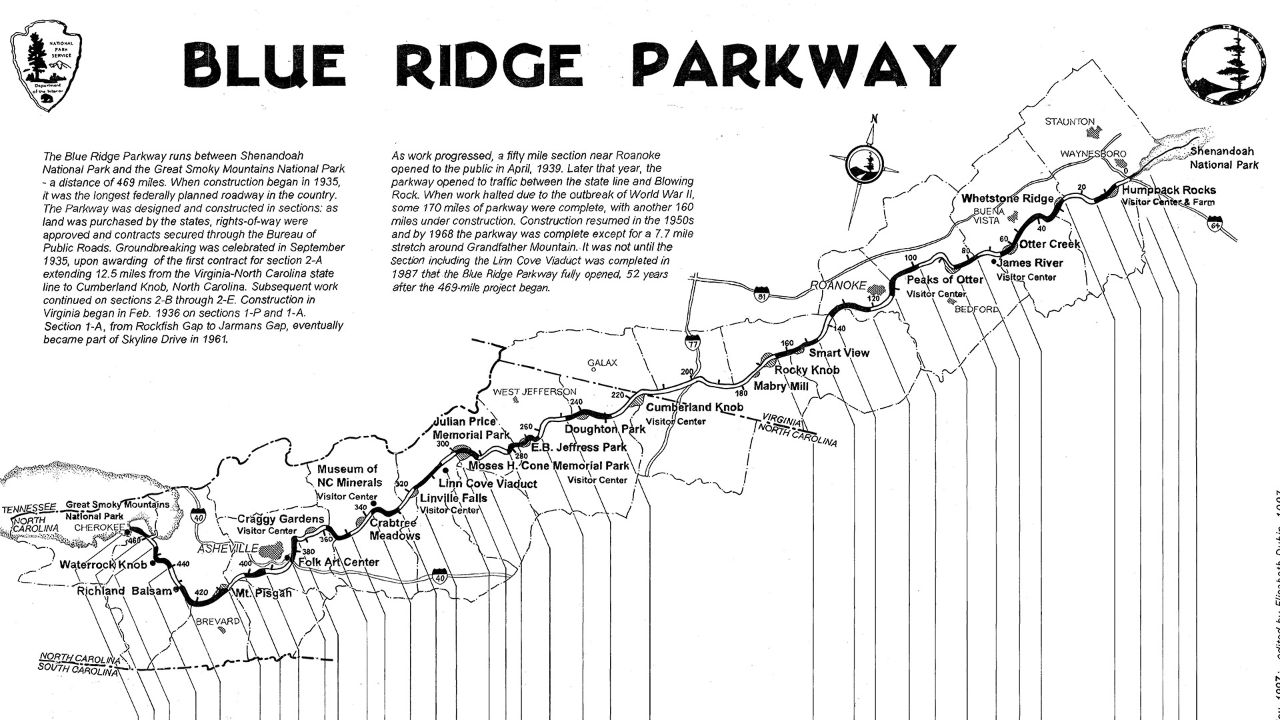

Most of the roads that we drive along have grown up for commercial reasons, to connect communities, factories, mines, ports and markets. The Blue Ridge Parkway is different. This 469-mile ribbon of highway was designed solely for one thing: the pleasure of touring by automobile. And by that the founders meant private automobiles. Commercial traffic, including the giant rigs that often clog America’s interstates, are not allowed. Nor are billboards. Or gas stations. Or strip malls. Or Motel 6s. It’s the highway reduced to its bare essentials: an unadorned two-lane blacktop, with nothing to distract you from the visual pleasures of the mountain country you are traveling through.

I drove it when I was in Washington D.C. with plans that had turned to dust in my iPhone and left me a week to kill. I bought a Rand McNally Road Atlas and there it was, a serpentine line wiggling down through Virginia and North Carolina to the Great Smoky Mountains on the Tennessee border. I had found the road trip I had been searching for, but in truth what I got was a fascinating slice through Appalachian history, not all of it comfortable. For, like all great public enterprises, the grandeur of the Parkway was, to some extent, built on the tears of others. But of course as a Parkway virgin, I didn’t know that when I rented my car and headed west from D.C. on busy Interstate-66 (not to be confused with Route 66), which slices through Virginia’s rolling horse country – take the alternative Route 50 through Middleburg to see it in all its white-picketed, Range Rover-ed, fox-hunting splendor.

THE SKYLINE DRIVE

"As you snake along it, you can’t help feeling that here was a wonderful combo of government works, social engineering and job creation, which is partially right. But the rest of the story, the darker part, had to wait a good few miles before I heard it."

The Skyline, like its sibling the Parkway, owes its existence to economic depravation, to the Great Depression that hit this region of western Virginia and the state of West Virginia particularly hard. In 1931, President Herbert Hoover authorized the building a spinal road along the Blue Ridge Mountains to create employment. The Skyline took nine years to build. As you snake along it, you can’t help feeling that here was a wonderful combo of government works, social engineering and job creation, which is partially right. But the rest of the story, the darker part, had to wait a good few miles before I heard it.

Mostly along the Skyline, especially at dusk, you worry about one thing – the wildlife, or rather, you coming into contact with said fauna. As you round one of the many, many bends, out of the trees and undergrowth might leap a suicidal deer or bobcat. Skunks, I found, tended to linger near the center of the road, as if their scent could deter even a set of Firestones. The carcasses dotting the tarmac suggested otherwise.

At Rockfish Gap, crossing Interstate-64, you reach the entrée – the Blue Ridge Parkway, where your right foot begins to twitch as you realize the speed limit is now a heady 45 mph. In fact, the switchbacks and the hairpins will make sure you rarely stray over that. This section of highway was started in 1933, with the first section unveiled in 1935 and the last, the Linn Cove viaduct crossing the Black Rock section of Grandfather Mountain, in 1987. It was conceived and sculpted by a 25-year-old engineer, Stanley W Abbot, who looked upon it as an undertaking that was part terra-forming and part giant artwork: "I can’t image a more creative job than locating the Blue Ridge Parkway," he once said. So the road is a mix of the functional and the slyly artistic, with many swoops, curves and tunnels clearly designed to give the most dramatic "reveal" of a craggy mountain, a dense forest or a vast panorama combining both, the craggy peaks swathed in woodlands like a thick fleece.

"There’s more to the Blue Ridge that just pretty scenery," she had said."

The communities that bracket the Skyline and the Parkway have become something of a fashionable locavore destination of late – the food scene is thriving in nearby towns like Staunton, Spruce Pine and Lexington and fashionable D.C., New York and Californian restaurants often use the artisan cider, cheese, beers, butter, wine and bread they produce. But food wasn’t on my mind. I had the radio tuned to Classic Country 98.1, and it was the Bluegrass Hour when I turned off the Parkway and headed for Floyd.

In truth, I didn’t know Floyd was on my itinerary when I left Washington. It was suggested to me when I stopped for lunch at the Skyline Lodge back on Skyline Drive (Like the Parkway, it has a handful of lodging/dining options actually on the route.) There, I fell into conversation with a waitress called Janet, who told me, in a twang that was pure Dolly Parton, that her family was Scotch-Irish settlers who had arrived back in the early 1800s and that I should head for Floyd to find some proper mountain culture, from the days before the Skyline and the Parkway. "There’s more to the Blue Ridge that just pretty scenery," she had said.

The town of Floyd is on another famous highway hereabouts — The Crooked Road, aka Route 58, which intersects the Parkway to the north of the Virginia/Carolina border. It links a series of small towns that, collectively, function as a repository of Virginia’s Appalachian culture. As suggested by Janet, I pitched up at Floyd’s Country Store, which is just what it says on the seed packet, although on Friday nights and on weekends the floor is cleared of sacks and tins and hardware and the place hums to the sound of banjo, fiddle, mandolin and dulcimer. There’s no alcohol served, but it turns out you can have a good old mountain time on endless coffee and pie. There’s music, there’s dancing and there is lots of talk.

I fell in with Ralph, a fiddle player from the nearby town of Ferrum, who told me a different tale of the Parkway to the usual one of landscape artist Stanley Abbot crafting a way through the wilderness. "Oh, there was a lot of opposition to the road, here and on the Skyline. My daddy used to tell me how some locals threatened to sabotage the construction. But they went ahead and moved families off the land, just so they could build a road to nowhere for Easterners to come and play on, that’s what he said."

"There was a human cost to creating this highway, just so I and countless others could drive along it. It was a long time ago, perhaps, but those still in the mountains appreciate it if you acknowledge it wasn’t something built from nothing."

The mountain people were subjected to compulsory purchase if they could prove they owned their plot, eviction if not. There were stories of deputies dragging off screaming women and children and homesteads being put to the torch as the graders moved in. Farmers complained that the ban on commercial traffic applied to their agricultural vehicles, indicative how the needs of locals were secondary to those of the future tourists. To keep public opinion on-side, government sources often described the inhabitants in disparaging terms. As one report put it: “[They are]…families of unlettered folk, of almost pure Anglo-Saxon stock, sheltered in tiny, mud-plastered log cabins and supported by a primitive agriculture … no community government, no organized religion, little social organization wider than that of the family and clan, and only traces of organized industry.” One of those organized industries being, of course, moonshine, which the government also disliked.

It was feared by the nearby communities that the "Displaced," as they were known, would take much of the unique Appalachian culture with them when they went. But places such as Floyd’s Country Store and the Blue Ridge Music Center at Milepost 213 on the Parkway and local artists like Doc Watson, the Carter Family, Earl Scruggs and more recently Gillian Welch and Alison Krauss (although neither are actually from around here) have kept the mountain’s musical traditions alive.

"I guess it worked out OK in the long run," said Ralph. "Because if they hadn’t made the park, I think all the big animals and a lot of the trees would’ve gone. Probably all be condos now. But people ought to know that folks did live here before the road came along, it wasn’t empty land."

The knowledge of this forced displacement didn’t tarnish my enjoyment of the road, but somehow deepened it. There was a human cost to creating this highway, just so I and countless others could drive along it. It was a long time ago, perhaps, but those still in the mountains appreciate it if you acknowledge it wasn’t something built from nothing. The high, lonesome sounds coming from my radio thereafter seemed to take on a fresh poignancy.

Soon after leaving Floyd I hit one of the road’s signature low clouds. It was a Foggy Mountain Breakdown (or at least slowdown) for real as I crawled south towards Asheville, thankful that there were no Mack trucks thundering up behind me, although I did spend many hours staring at the tail lights of an RV until I reached the turn-off for Asheville.

I had been to Asheville many years before, on the trail of F. Scott Fitzgerald. He had spent the summers of ’35 and ’36 at the vast Grove Park Hotel, a broken man plagued by alcoholism and tormented by thoughts of wife Zelda in her nearby mental asylum (where she would die in a fire in 1948, eight years after a heart attack took her husband). On that occasion, Asheville looked as if it had had the heart ripped out of it, with a downtown that was desolate and depressing. Now, it is a thriving mix of coffee shops, antique stores, farm-to-fork restaurants, live music bars and one of the best places along the way to spend a few days.

The Parkway terminates at the entrance to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park of Tennessee, which really do have a smoky haze hanging over them from the volatile organic chemicals that leach out from the vegetation. It’s a whole other world in there, with unique ecosystems and plant life, but my drive was done. I turned east and headed for the airport at Charlotte, North Carolina, back to the reality of Big Macs and big Macks, the sound of fiddles and laments fading with every mile.

Days of The Dead

Death seems like a rather unlikely occasion for an elaborate celebration, but many religions and communities around the world hold annual events dedicated to the passing of life.

Take an Autumn Drive from New York to Vermont

If you find yourself in New York in the autumn with a day to spare, consider this a scenic drive north.